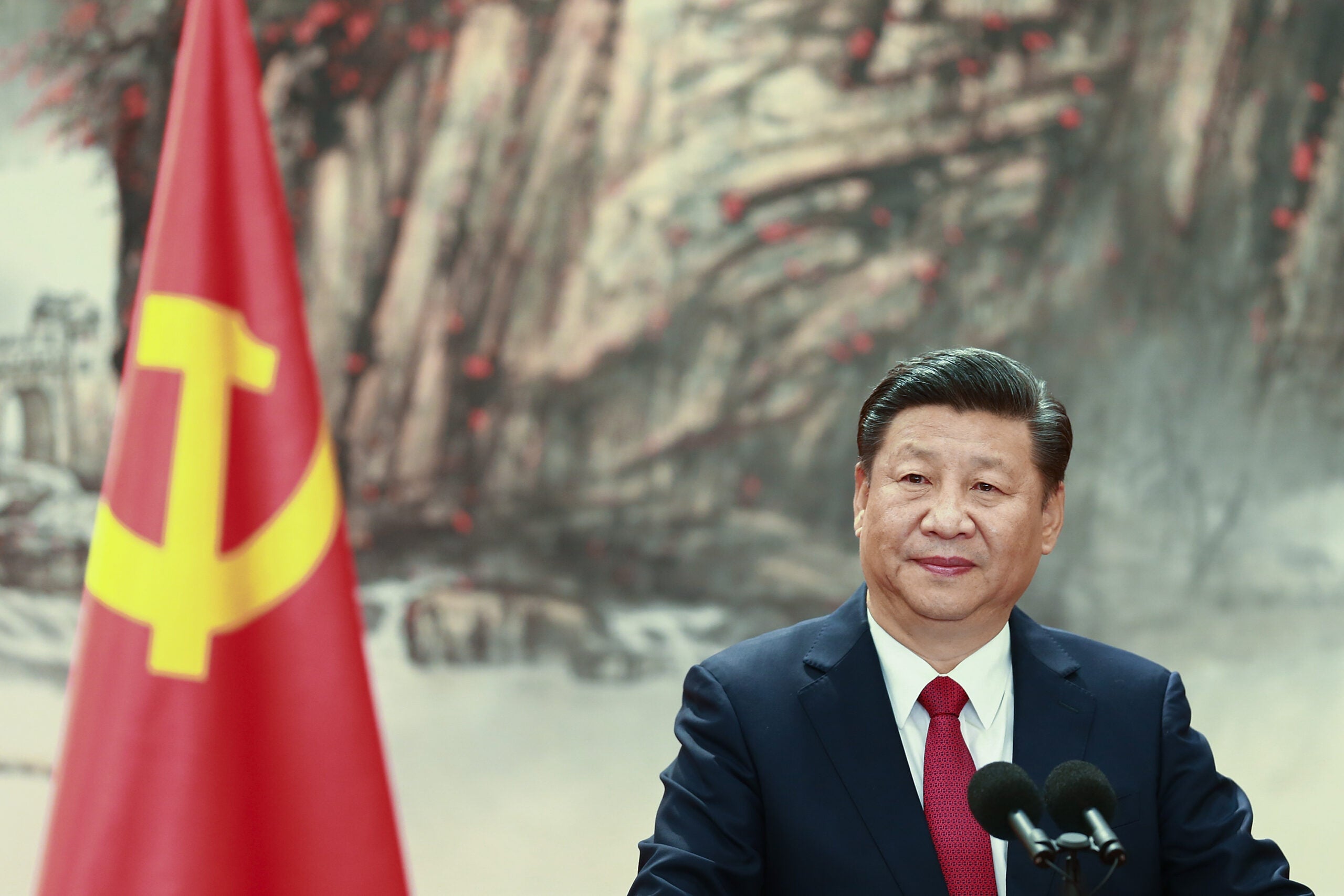

After four decades of following Deng Xiaoping’s ideology that it is acceptable for some Chinese to “become wealthy first”, President Xi Jinping has now taken a drastic turn away from that maxim with the new objective of “common prosperity”.

Following the headline-making crackdown on China’s tech industry, Xi touted in an August 17 national speech that China would go back to basics, envisioning a society less for the rich and more for the poor.

He emphasised that “common prosperity is an essential requirement of socialism and an important feature of Chinese-style modernisation.” He also highlighted the necessity for China “to adhere to a people-centred concept of development.”

As a result, China’s Communist Party (CCP) aims to create a more equal society, with an “olive-shaped” system of wealth distribution set to benefit the middle class and rural areas more.

China has long been one of the most unequal major economies in the world, with one common measure of income inequality, the Gini coefficient, at 0.465 in 2019 according to official data out of a possible 1.0.

“After the reform and opening up, our party profoundly underwent both positive and negative historical experiences, realising that poverty is not socialism. We broke the shackles of the traditional system and allowed some people and some regions to get rich first,” an official statement lamented.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe wealth gap is even more staggering. The richest 20% of Chinese enjoy a disposable income more than ten times as high as the poorest 20%. Disposable incomes are two-and-a-half times higher in cities than in rural areas. In addition, the top 1% own 30.6% of household wealth, according to Credit Suisse.

This has led to soaring house prices in urban areas and an overall higher cost of living. As a result, many young people have embraced the neo-Taoist ideology of laying low – known in Chinese as ‘tang ping’ – opting out of the rat race by not being ambitious, not working hard and not wanting to get married or have kids.

“At its core is the rising and serious issue that growing numbers of urban middle class Chinese born after 1990 find life too much of a hassle and too costly to want even one child as the uninterrupted trend line signals the ‘Japanification’ of China by 2050,” explains Michael Orme, senior analyst at GlobalData and a China specialist.

Business of prosperity

Xi’s speech emphasised a need to “regulate excessively high-income groups” and said that businesses should return more of their profits to society. This announcement has prompted big firms to scramble to demonstrate their loyalty to the party.

A day after Xi’s speech, Tencent pledged that it would set aside 50bn yuan ($7.7bn) for a “common prosperity” fund. “As a Chinese technology company that has matured amid the tide of reform and opening up, Tencent is constantly thinking about how to rely on its technology and digital capabilities to help society’s development,” a company statement read.

Soon after, ecommerce giant Pinduoduo said it would donate 10bn yuan ($1.5bn) to expand agricultural projects in rural areas. “Investing in agriculture pays off for everyone because agriculture is the nexus of food security and quality, public health and environmental sustainability,” chairman and CEO Chen Lei said in a call as recorded by Nikkei Asia.

Perhaps surprisingly, the announcement prompted the company’s shares to jump by 22%, on the assumption that it demonstrated both willingness and the financial ability to go along with the CCP.

Most recently, Alibaba pledged to set aside 100bn yuan ($15.5bn) towards China’s “common prosperity” goal, making it the biggest single corporate pledge to narrow the nation’s wealth gap yet. The company said that the allocation would be disbursed before 2050 to promote investments in technology, support small businesses, foster development in rural areas, help small businesses expand overseas and improve the welfare among gig economy workers, including delivery people and drivers.

According to GlobalData’s database, Tencent reported revenues of $69.9bn in 2020. A $7.7bn charitable donation thus reflects roughly 11% of the company’s annual income.

In contrast with Pinduoduo’s 2020 revenue numbers of $8.6bn, $1.5bn constitutes about 17% of the ecommerce platform’s proceeds.

Alibaba reported revenues of $104bn in 2021. Its $15.5bn pledge therefore reflects approximately 15% of the company’s yearly earnings.

Although it is difficult to compare the amount of money set aside by the different tech giants, as the timeframe within which these funds are to be distributed differs, the current trend shows that companies are expected to donate between 10% and 20% of their yearly revenue.

Meanwhile, former ByteDance CEO Zhang Yiming, Pinduoduo founder Colin Huang and Xiaomi CEO Lei Jun have vowed to donate much of their personal wealth. Five of China’s tech billionaires have pledged at least $13bn of their private fortunes to charitable foundations and initiatives, a sum that far exceeds previous years’ totals, according to Fortune magazine.

Wang Xing, the founder of food delivery service Meituan also joined the group of tech CEOs vowing to tackle inequality. He told investors that “common prosperity” was “built into the genes” of his company.

Although the company did not make any monetary promises, Wang did say that Meituan would “continue to actively implement compliance requirements, improved internal control mechanisms across all businesses, conduct in-depth self-reviews and actively rectify issues to ensure full business compliance.”

Xi’s mounting campaign for “common prosperity” has sent shock waves through the economy, triggering market sell-offs and speculation that China will reverse reforms that have lifted incomes nationally and created a class of powerful billionaires.

“Businesses, including foreign businesses operating in China, will need to be seen to contribute to ‘common prosperity,” Orme points out. He added that, for foreign companies, this could be seen as an extension of the need to comply with the conditions of China’s social credit system.

The arbitrary meaning of “common prosperity”

The notion of “common prosperity” is hardly a new one in China. It was first advocated for by Mao Zedong in his 1953 “Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Development of Agricultural Production Cooperatives”. Even Deng Xiaoping followed the concept of “common prosperity”, albeit allowing for the fact that some would get rich first, while others would follow.

Although the idea may not be new, it is newly important. Xi mentioned the words “common prosperity” 65 times in speeches and high-level meetings in the first eight months of 2021, according to Bloomberg.

He reintroduced the concept as part of his vision for a socialist system with Chinese characteristics. In December 2020, Xi vowed to prevent the “disorderly expansion of capital”, or in other words, the unhindered “growth at the expense of the public interest”.

This also ties in with Beijing’s ongoing crackdown on big business. The notion of equal wealth distribution is supposed to even out the concentration of money, social power and data in the hands of a small group of companies, entrepreneurs and financiers.

The resignation and disappearance from the public eye of some of the country’s most powerful internet moguls shows that there is already progress towards the second goal: that is, cutting the tech billionaires and their companies down in size.

“I really do think a second Cultural Revolution is underway in China without which Xi’s CCP could be in jeopardy, increasing control of internal data flows and of Big Tech notwithstanding,” Orme says.

The “common prosperity” ideology has resulted in an increasing number of regulations to protect the Communist Party’s vision of the common good and induced self-correcting behaviour among Chinese billionaires and large firms. It is the revival of Chinese socialism imposed upon market-based modernisation which makes it especially hard for investors to interpret.

Unlike regulations in the West, which often simply seek to curb practices that can destabilise market efficiency, Chinese regulations aim to inject a sense of fairness into economic practices. This definition of fairness is viewed through the lens of the CCP and particularly through the eyes of Xi Jinping.

Most socialist governments employ some wealth redistribution methods with taxes and transfers. However, China’s approach reaches further. It is also championing two other kinds of redistribution: “voluntary” contributions and so-called “pre-distribution”.

This entails altering the split of national income between wages and profits. A labour share is, however, not easy to measure, let alone manipulate. Xi’s ambitious plans, therefore, make it difficult for investors to gauge the long-term effects of China’s “common prosperity” goals.