It’s hard to resist the familiar ping of an incoming email, the red notification on your Facebook app or the buzz of a text message.

Screens are everywhere. Our phones wake us up in the morning, our laptops get us through our day at work, and our televisions keep us entertained in the evening.

With a few clicks we can stream movies from Netflix, order food from Deliveroo, scroll through potential love interests, book a weekend away, listen to music on Spotify, and read the latest news.

Whether we are using them for business or pleasure, smartphones, tablets and laptops cater to our every need.

We are increasingly dependent on these portable electronic devices, but do manufacturers, tech giants, governments and schools have a responsibility to help combat excessive screen time?

If they don’t, do we run the risk of becoming digital addicts. Or are we already?

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataHow we define addiction is important

Mark Griffiths is a professor at Nottingham Trent University and a chartered psychologist specialising in behavioural addictions.

Griffiths was the first academic to write about internet addiction back in 1996, but insists that the term itself needs to be understood better.

He tells Verdict:

People are no more addicted to the internet as alcoholics are addicted to the bottle. So really what we’re talking about are addictions on the internet, rather than an addiction to the internet. Yes, online addictions are on the rise, but it’s a case of asking whether the gambling addicts of 30 years ago are now just doing their vice of choice online because it’s more convenient.

In 2016, the UK’s gambling advertising spend hit £312m, data published by research firm Nielsen revealed.

Over the next 12 months, more than half of the revenue generated by gambling businesses operating in Britain will be online, according to Kate Lampard, chairwoman of the charity GambleAware.

But does doing something excessively qualify as an addiction?

Griffiths says:

I don’t want to take away from the fact that there are young people out there who are genuinely hooked on various activities online but the vast majority are engaged in habitual use not addictive use.

To meet the criteria of addiction, a person’s internet use must completely take over their lives, compromising their relationships, their health or their work.

When you get to the heart of what an addiction really is, the good news is that very few people are genuine online addicts.

How much is too much?

The average internet user in the UK spends 25 hours a week online and checks their phone 200 times a day — that’s once every six and a half minutes, according to a report published last August by Ofcom, the communications regulator.

Around a third of users said they had missed out on socialising with friends and family as a result of spending too much time online, while a quarter of teenagers admitted that they’d been late for school due to excessive internet use.

A quarter of people even said someone had bumped into them in the street because they were too busy looking at their mobile phone.

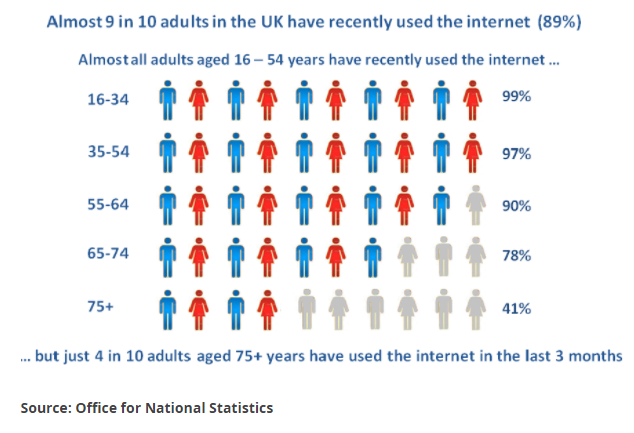

In the first four months of 2017 alone, 99 percent of all adults aged between 16 and 34 described themselves as recent internet users, according to the latest figures published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

On average, British children own their first mobile phone by the age of seven, a tablet at eight and their first smartphone by ten, according to a consumer survey published last year by Opinium.

They start browsing the internet as early as age five.

More and more primary and secondary schools are introducing measures to stop pupils from using their phones in the classroom, but no formal legislation at the government level has been introduced anywhere in the UK.

A study published by the London School of Economics (LSE) in 2015 found that banning mobile phones adds the equivalent of an extra hour a week, or five days worth of learning to the school year.

Even though there is evidence to suggest that mobile phone bans in the classroom are beneficial, the majority of schools are guilty of fostering a reliance on screens.

Earlier this month, the Scottish Conservatives called for a ban on mobile phones in Scotland’s primary schools.

The Scottish government refused:

Head teachers can already ban phones in school if they wish to, however phones are now being used effectively in classrooms to aid learning.

Anya Kamenetz, a Brooklyn-based education expert and the author of The Art of Screen Time believes schools should be looking at different ways to help children learn that don’t always involve electronic devices.

Kamenetz says:

Schools are rushing to adopt screens. After all, even to do their homework children usually need to use laptops.

For the past five years, Tanya Goodin, who describes herself as a digital detox evangelist, has been giving talks at schools across the UK on the importance of limiting screen time.

The author of the self-help book Off, a guide to disconnecting from the virtual world, tells Verdict that she is regularly approached by parents concerned about the amount of time their kids spend using various digital gadgets, particularly smartphones.

When I talk to parents, I say very firmly there’s no reason for a child under 13 to have a smartphone — they can have a Nokia 330. I just don’t believe kids can regulate their own smartphone use.

Are parents doing enough?

So many parents shy away from the normal parental controls over screen time that they are happy to impose on drinking alcohol, doing drugs and going out late. They are worried they’ll come across like Luddites — that somehow limiting screen time means they’re not up-to-date with the teenage generation.

She adds, however, that an increasing number of parents are contacting her to ask how many hours they should let their children sit in front of a screen.

Four hours is probably the daily limit; that’s certainly what psychiatrists have told me.

Are tech giants shying away from their duty to society?

It’s not just parents and schools who have a responsibility to ensure digital devices don’t consume too much of our time, according to David Greenfield, founder of the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction.

Greenfield tells Verdict:

I think smartphones should have a warning saying: this technology can be addictive and distracting. Cellphone manufacturers and the technology companies that provide internet and data services do have a responsibility to educate the consumer. That hasn’t really happened yet and these big companies will not do anything until they are forced to.

Goodin agrees that tech giants like Apple and mobile phone companies cultivate an over-reliance on the products they sell.

Remember designing the software and hardware that we’re putting in our pockets is a billion dollar industry.

How are big corporations able to absolve themselves from any responsibility?

Kamenetz says:

I think they’ve been able to hide behind the inconclusiveness of the evidence for too long. The truth is that numerous studies have shown that spending too much time on screens can contribute to ADHD, sleep deprivation, anxiety, depression and other mental health problems, but it’s easy to point to other factors.

In an article published in The Atlantic Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University cites evidence that teens in the US who spend three hours a day or more on electronic devices are 35 percent more likely to have a risk factor for suicide.

Corporations should be doing more to combat our growing dependency on electronic devices, says Adam Alter, a professor of marketing at New York University’s Stern School of Business, and the author of Irresistible, an investigation into why the digital world is so appealing.

But who should be putting pressure on tech companies?

Alter tells Verdict:

I think governments should intervene — not so much by regulating consumption, but by changing how companies and producers behave. Drugs laws tend to punish dealers and distributors more harshly than users, and that’s because you have far more sway over a large scale problem if you target the source of the problem, rather than end-users.

The UK government has not even issued recommendations on screen time limits, so it seems unlikely that strict legislation on internet use will be introduced in the near future.

Meanwhile, the growing number of apps, podcasts, interactive games, online streaming services, and new features on social media platforms will only make it harder to avoid the pull of the so-called plugged-in economy.

In turn, we could see the proliferation of internet addiction treatment centres if we fail to rein in our desire for instant gratification and convenience.

Although there are only a handful in the US and the UK, Greenfield’s centre in Hartford County, Connecticut is about to launch its first residential program in response to rising demand for more intensive therapy.

The 300 military-style internet treatment camps in China should serve as a warning to the west of just how bad things could get.