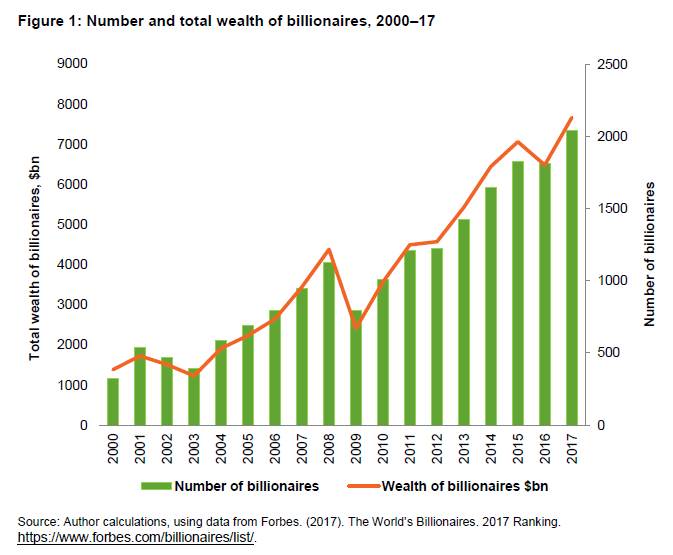

In the 12 months to March 2017 billionaire fortunes grew by £585bn — enough to end extreme poverty more than seven times over.

That’s according to the Oxfam Inequality Report, released ahead of the World Economic Forum in Davos this week. It found 82 percent of the all the wealth generated globally last year went into the bank accounts of the richest one percent of the population.

Mark Goldring, Oxfam GB chief executive, said:

Something is very wrong with a global economy that allows the one percent to enjoy the lion’s share of increases in wealth while the poorest half of humanity miss out. The concentration of extreme wealth at the top is not a sign of a thriving economy but a symptom of a system that is failing the millions of hard-working people on poverty wages who make our clothes and grow our food.

The real increase in global wealth between July 2016 and June 2017 was $9.2trn, of which $7.6trn (82 percent) went to the top one percent of the population and the remainder to the rest of the top 20 percent.

Billionaire wealth rose by an average of 13 percent a year between 2006 and 2015 – six times faster than the wages of ordinary workers.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataRead more: What the richest ten speakers at Davos are worth

Last year saw the biggest increase in the number of billionaires in history, one more every two days. There are now 2,043 dollar billionaires worldwide, with nine out of 10 men.

Over three-quarters of people either agree or strongly agree that the gap between rich and poor in their country is too large – this ranges from 58 percent in the Netherlands to 92 percent in Nigeria according to an Oxfam survey of over 70,000 people in 10 countries.

Calculations are based on global wealth distribution data provided by the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Data book 2017. The wealth of billionaires was calculated using Forbes’ billionaires list last published in March 2017.

The richest verses the poorest

With wealth of $54.4bn, Carlos Slim is the sixth richest man in the world and the richest in Latin America, according to Oxfam.

His vast fortune derives from an almost complete monopoly that he was able to establish over fixed line, mobile and broadband communications services in Mexico. An OECD report in 2012 concluded that this monopolisation has had significant negative effects for consumers and for the economy.

While competition reforms in 2013 introduced fairer prices and improved service provision, the wealth Carlos Slim amassed in part because of this monopoly continues to grow, as he has diversified his investments in the Mexican economy.

Slim’s net wealth increased by $4.5bn between 2016 and 2017. This amount is enough to pay the annual salaries of 3.5m Mexican workers on the minimum wage.

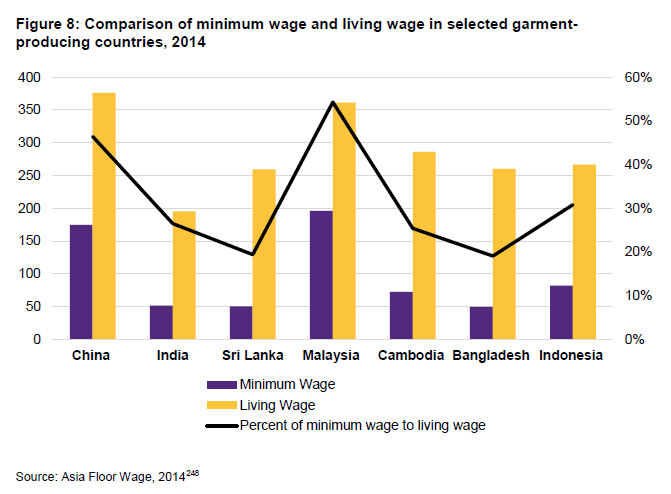

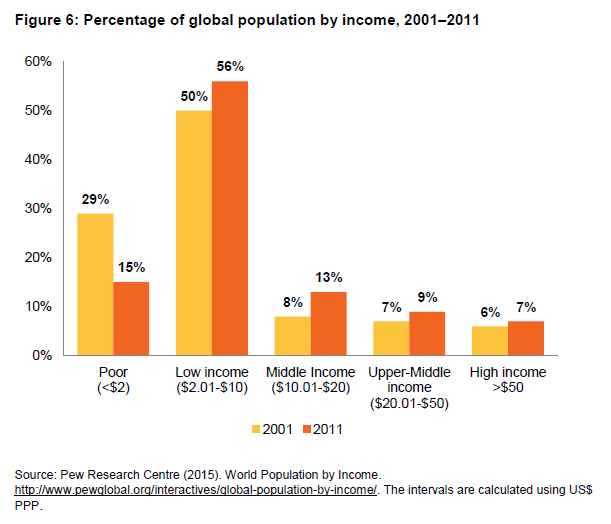

Meanwhile, around 56 percent of the global population lives on between $2 and $10 a day, with recent estimates by the International Labour Organization showing that almost one in three workers in emerging and developing countries live in poverty.

Poverty wages in turn have knock-on impacts, with workers consistently working long hours of overtime just to earn enough to survive.

While the value of what workers produce has grown dramatically, wages have not kept pace.

The ILO has found that, in 91 of 133 rich and developing countries, wages have not kept pace with increased productivity and economic growth from 1995–2014.

After the global financial crisis of 2008–09, growth in real wages at the global level recovered in 2010, but since 2012 they have decelerated, falling from 2.5 percent to 1.7 percent in 2015, the lowest level in four years.

The minimum wage

Myanmar had no legal minimum wage in place, before September 2015.

Some workers were earning as little as $0.60 a day as a base wage, taking on long hours of overtime, including forced overtime.

In 2012, workers held mass strikes in protest. Following more than two years of negotiations between unions, employers and the government, a new minimum wage ($2.70 for an eight-hour work day) was announced.

When the government increased this by the end of 2015, it had the potential to increase earnings for the 300,000 workers in the garment sector by nearly $80m a year.

Multinational companies that source garments from Myanmar supported the implementation of the minimum wage, showing how they can act as a force for good.

Pay inequality in numbers

-

In 2017 it took just three days for the UK’s top bosses to make more money than the typical UK full-time worker will earn all year, according to the High Pay Centre.

-

In Nigeria, the legal minimum wage would need to be tripled to ensure decent living standards.

-

In the 12 months to March 2017, billionaires’ fortunes grew by a staggering $762bn — enough to end extreme poverty more than seven times over.