In an age where Facebook seems to know everything and big data controls the planet, the world can look pretty scary. Still, if it’s any consolation, none of our current troubles are novel. In fact, they have been the subject of novels.

For generations, science-fiction writers have been predicting the future. Most of these predictions have proved false, of course. We’re not jetting about in flying cars, twirling sonic screwdrivers, or battling triffids in the wild. Still, plenty of predictions made in science-fiction have proved accurate.

Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel Snow Crash was reportedly once required reading for new recruits at Facebook and is one of a number of works of fiction that seem to speak directly to the way social media has changed our lives. Here are a few of the others and some of the lessons we should learn from them.

Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson (1992):

There’s no denying that Snow Crash is more timely than ever. Plus, with an Amazon TV series on the way helmed by Ant-Man writer Joe Cornish, there’s never been a better time to read this classic work of science-fiction literature.

The early 21st Century, sometime around now, is Snow Crash‘s setting. The US no longer exists after various private organisations and enterprises ceded control of territory. Much of the action takes place in a virtual reality successor to the internet called the Metaverse. Digital avatars represent all the users. (2011 novel Ready Player One, which has recently been adapted into a film, borrowed liberally from Snow Crash.)

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe novel’s plot sees a tech entrepreneur attempting to infect people’s brains with malware using some ancient religious macguffin.But what’s much more interesting is what happens behind the plot.

There are plenty of examples of modern technology that Snow Crash predicted. These include crypto-currencies like bitcoin, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality hangout spaces. In the novel’s future, couriers carry all mail, eerily similar to the accusations Trump has made about Amazon in recent weeks. There’s also an intelligence agency who have unfettered access to everyone’s private data.

Arguably the most prescient element of the novel is the government’s failure to legislate to curb the technology which controls the world. At one point, the villain of the novel notes:

“Y’know, watching government regulators trying to keep up with the world is my favourite sport… It’s like if they figured out a way to regulate horses at the same time the [Ford] Model T and the airplane were being introduced.”

Now what does that remind you of?

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953):

Another science-fiction dystopia is coming to television in 2018. Funny how that keeps happening.

So what does a novel published in 1953 have to say about life for the Facebook generation? Well, broadly, the novel discusses information and its dissemination. Facebook’s ‘pivot to video’ could be read as a direct parallel of the societal ills suggested by Fahrenheit 451.

The novel tells the story of Guy Montag, a fireman whose job is to burn books. Books are illegal in the dystopian future America because people were more interested in film and television, social networks, fast cars, and drugs. As a result, books were banned by minority groups. They argued books contained controversial and outdated content.

There are certainly parallels between the idea of trigger-warning and safe-space culture. However, for social media users, one element of this novel should be more worrying than any other. At one point, Montag’s boss, Captain Beatty tells him that books became unpopular in the first place because they were endlessly abridged and simplified to become mindless entertainment designed to please but never challenge the masses.

Consider, in comparison, ‘news videos’ favoured by Facebook’s algorithm. These are short chunks of footage, often no longer than a minute designed to explain complex or long-winded problems. Often, these videos divorce their subjects from context to dumb down or oversimplify their content.

Also, there’s the issue of viral media. In Montag’s world, people don’t care about information. Montag’s wife and her friends have next to no interest in politics or an oncoming war. Instead they are purely focused on entertainment. Compare this to Facebook where entire media brands have built up followings of tens of millions of people by sharing viral, ‘shareable’ content.

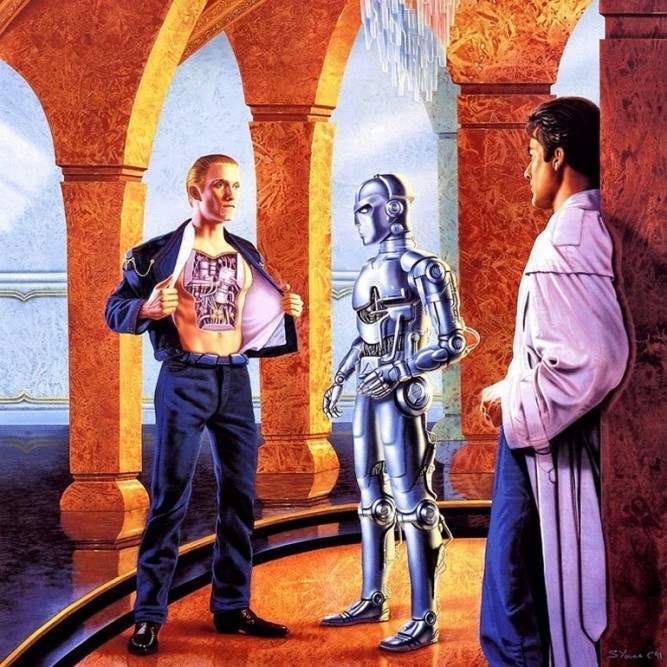

The Naked Sun by Isaac Asimov (1957):

The insight of The Naked Sun on the Faceook generation isn’t quite as complex or novel as the aforementioned examples, but it is worth noting.

The Naked Sun actually might be one of the first ever science-fiction novels to predict social media and its place in the world.

Set on the planet Solaria, the book is a detective story. Earth-born detective Elijah Baley has to investigate the murder of Rikaine Delmarre on Solaria. The planet has a population of 20,000 humans but AI-controlled robots vastly outnumber them. He finds a society where people view face-to-face conversation as dirty. Instead, Solarians communicate via holograms and social networks.

This mode of communication allows Solarians to edit their features and personalities to tailor the way they present themselves. Obviously, there’s a very pronounced comparison with modern social media, in that sense.

There’s also some fun stuff about how nudity is perfectly normal and accepted online but not in reality. Perhaps that one is more similar to Tumblr than Facebook, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

The Machine Stops by E.M. Forster (1909):

Writing for Slate, Lawrence M. Krauss, director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University, noted that science-fiction writers never really predicted the internet.

Still, The Machine Stops is about as close as it gets to the internet in early science-fiction.

In the world of The Machine Stops humans live underground, completely alone and isolated in individual rooms. Like the Solarians in The Naked Sun, they avoid contact with others as a matter of course. The entire purpose of humanity is to share their ‘ideas’ and discuss them.

Meanwhile, the Machine, a robotic artificial intelligence, cares for all the humans and tends to their physical and spiritual needs. Eventually, the people begin to worship the Machine. They begin to view the Machine as omnipotent and neglect to fix the processes which keep the machine functioning.

Obviously there is a parallel to our modern dependence on Facebook and the internet at large. But perhaps, more broadly, the humans’ choice to view the Machine as omnipotent and avoid repairing it speaks more generally to society’s unwillingness to challenge Facebook or act in our own interest against the company’s technology. For example, the Senate’s decidedly soft-ball questions to Zuckerberg at the recent hearing, or the failure to legislate for the internet.

There’s also probably plenty to say about the modern obsession and worship of artificial intelligence.

The Atrocity Exhibition by J.G Ballard (1970):

Arguably the most challenging of the books on this list, The Atrocity Exhibition is an incredibly convoluted book. While some scholars describe it as a novel, others contest this description.

Each of the book’s chapters takes the form of a short story or a ‘condensed novel’. Overall, the book follows a doctor at a mental hospital, as he navigates a mental breakdown. The main character reconstructs various different events and people in his mind. He attempts to twist their narratives to give each more personal meaning.

But what does that have to do with the internet and the Facebook generation? Well, it all hinges on the way Ballard envisaged the future.

The solipsistic, self-centred way the protagonist of The Atrocity Exhibition attempts to view history is similar to how Ballard believed humans would view the world in the future. In an essay for Vogue, he wrote:

“Every one of our actions during the day, across the entire spectrum of domestic life, will be instantly recorded… a computer [will be] trained to pick out only our best profiles, our wittiest dialogue, our most affecting expressions filmed through the kindest filters, and then stitch these together into a heightened re-enactment of the day… each of us within the privacy of our own rooms will be the star in a continually unfolding domestic saga, with parents, husbands, wives and children demoted to an appropriate supporting role.”

Essentially, Ballard predicted the future of social media. The world and the news are constantly refracted through seven billion personal views of it on social media, each with the person making them as the star.

In an interview with ID in 1987 he said:

“In the media landscape it’s almost impossible to separate fact from fiction.”

Fake news, anyone?