From fake news to Facebook, WhatsApp has attracted the media spotlight for a number of reasons. However, the service over the past six or so years has seen a dramatic shift in perception from those who are in power, changing from a subject of ire to Westminster’s primary communications platform. So how has WhatsApp changed Westminster?

WhatsApp has around 1.5 billion users although not all are equal; some use the service for keeping up with friends, while a select bunch are using it to run the country. Increasingly the app has become an invaluable tool in the corridors of government, but why has WhatsApp become so popular with politicians?

Political journalist and author of Haven’t You Heard? Gossip, Power & How Politics Really Works, Marie Le Conte, detailed the effects WhatsApp has had in Westminster, telling Verdict:

“It’s hard to overstate just how much WhatsApp has changed the way Westminster functions, at most levels. These days, journalists mostly communicate with MPs via WhatsApp; they receive a line from spinners via WhatsApp; MPs talk to each other in WhatsApp groups.”

This top-down communication has streamlined the Westminster process, making it much quicker to receive information from MPs. Unlike some digital disruptors that affect a certain industry sector, WhatsApp, like its wide adoption within the general public, has become used en-masse in parliament.

WhatsApp in Westminster: From chats to political power plays

The messaging service was critical in some Conservative MPs attempts to topple the former PM and has become a useful tool for MPs to get their message out.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

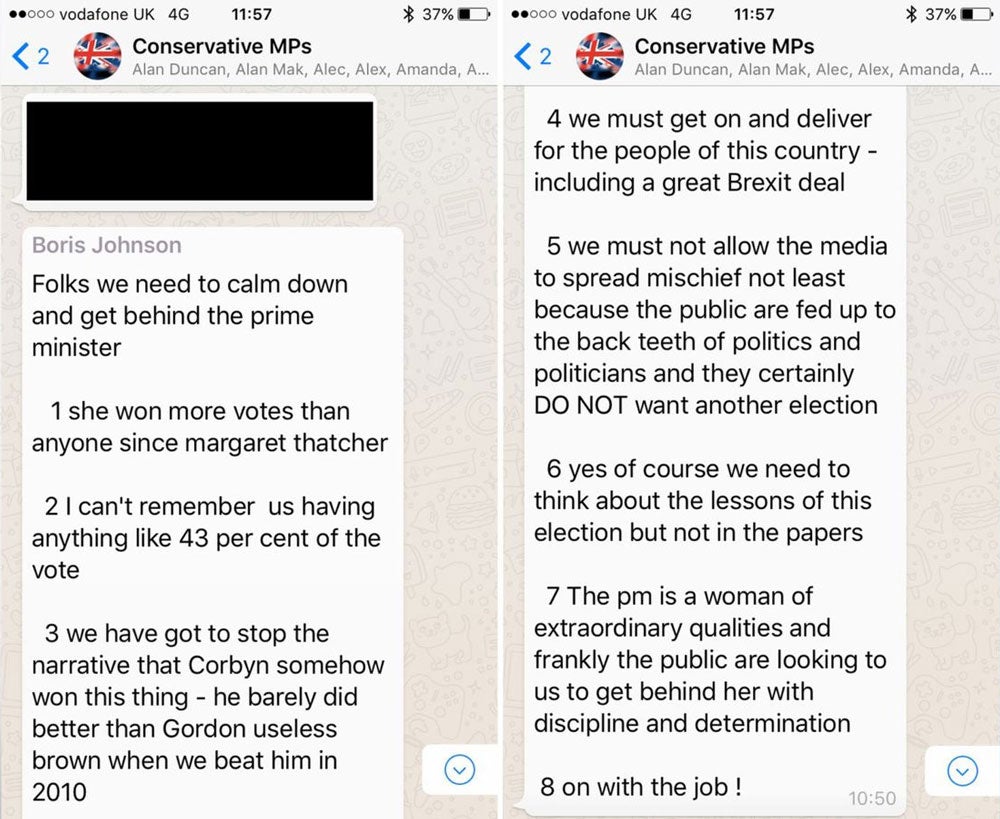

By GlobalDataSay something in a WhatsApp group and wait until it makes its way into the hands of the press, just as now-Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s message in support of Mrs May in 2017 saying “folks we need to calm down and get behind the prime minister” did.

More recently as the Conservatives fired 21 MPs for voting against the government, Rory Stewart said his sacking came via text, and later a Conservative MP and ‘administrator’ of the WhatsApp group politely requested that former ministers and colleagues remove themselves from the group.

One of the most-discussed Westminster WhatsApp chats is that of the European Research Group, the eurosceptic wing of the Conservative party. The groups’ chat was instrumental in rallying MPs against the withdrawal agreement and communications from the group were frequently leaked. Ian Duncan Smith’s messages in the group in 2018 urging colleagues to show party unison found their way into the hands of Buzzfeed, which revealed hundreds of messages sent in the group.

It isn’t just the Tory’s using WhatsApp, though: the opposition benches are also employing the service and again have also not been without their issues. Labour’s Lucy Powell was forced to apologise after criticising Angela Rayner and Tulip Siddiq. Powell fell afoul of an affliction most are familiar with: messaging the wrong chat.

Leaks from WhatsApp are interesting in that unlike those of the past which would cause damage, messages finding their way from WhatsApp to the press – like Boris’ leaked message – can often be to the benefit of the person who sent the message.

“I think that there were a few solid months of genuine group leaks when everyone moved to WhatsApp but the vast majority of MPs got smart about it quite quickly, and will now only posts things in groups they don’t fully trust if they don’t ultimately mind those things getting out,” Le Conte added.

Political leaks are nothing new, simply the medium of delivery has changed.

How WhatsApp is changing the pace of communication in Westminster

The instant aspect of the app is part of its charm: Politicians no longer need to send aides running around government buildings to get messages across and agree on lines to tell the press. The ability for whips – people who assert the party line – to quickly put their foot down and get everyone on-message is vital in an age where stories spread through social media like wildfire.

“The most useful thing about it is [that] it is remote and quick to use, so when events are unfolding you can plan campaign actions even if you’re miles away from each other in different constituencies,” Patrick Jenkins, London regional organiser at Labour for a people’s vote, told Verdict.

This seamlessness en-masse, regardless of location, makes the platform a far better way to coordinate on a national scale than conference calls and e-mail chains ever could.

Le Conte explained how WhatsApp has moved from bars and clubs of Westminster to group chats:

“You used to be able to gather that intel by doing the rounds in the bars and cafeteria of Parliament, but it’s now easier for people to plot on WhatsApp, so we often don’t even know which combinations of MPs are working together.”

For the press, knowing what’s going on in Westminster meant walking around and figuring out who was spending time with who. But with the push to online, MPs can keep their cards much closer to their chests.

Security concerns around WhatsApp

This freedom and security, however, isn’t without its downsides.

The Conservative Party in June investigated comments on a group chat against MP Antoinette Sandbach. A member of the party told Sandbach “You too are a disgrace. Time you left the party I think” in response to her views on the EU. Sandbach shared the messages in a now-deleted tweet, but they were up long enough to receive national attention and that of Conservative party leadership.

Encryption is another reason MPs trust WhatsApp as a method to communicate. The service’s end-to-end security means that only the sender, receiver and possibly particularly eagle-eyed onlookers can read what is said.

This gives MPs the ability to speak freely, rather than in hushed tones, as long as they trust who is on the other end of the phone. Unless leaked, MPs’ WhatsApps messages stay out of the public eye, with only one exception being if they concern government business. In this case, the usual Freedom of Information act rules apply.

This was confirmed by MP Oliver Letwin in 2016 when responding to a question about WhatsApp in the commons, saying:

“I hesitate to admit to my Honourable Friend that I have never personally used WhatsApp in my life. I am happy to reassure him that all aspects of Government business are properly recorded and minuted, and are subject to FOI requests as normal, despite the rumours that he has heard.”

A tool for political journalists

WhatsApp isn’t just a valuable tool for MPs: it also serves a similar purpose for the journalists who line the halls of Westminster.

With instant contact and the ability to send the same message to different people, a journalist can quickly sample the views of the entire commons, a practice detailed by Le Conte:

“Some journalists, for example, have been known to fire off the same request for comment or reaction to every MP in their contact book, thus being able to write a piece on how Parliament feels about a given issue near immediately”.

This reaffirms WhatsApp’s place as a powerful tool in Westminster, allowing those who shine a light to power to quickly asses if bills will pass and gain an overall mood of a party going into the House of Commons. Although MPs can hide their plotting more easily by taking it onto messaging services, they are also more accessible, with the app extending the same benefits of private conversations between colleagues to reporters.

Parliament is an old institution, with even older precedents, yet this unlikely technology incubator has become a flourishing ground for WhatsApp. The service has become firmly rooted in political communications and does not look like it is going anywhere for now.