For many young adults, nerves will be rife this morning. After all the excitement of A level results day last week, now it’s time for the GCSE results.

However, unlike in previous years, there’s some huge changes to the results school leavers will receive today.

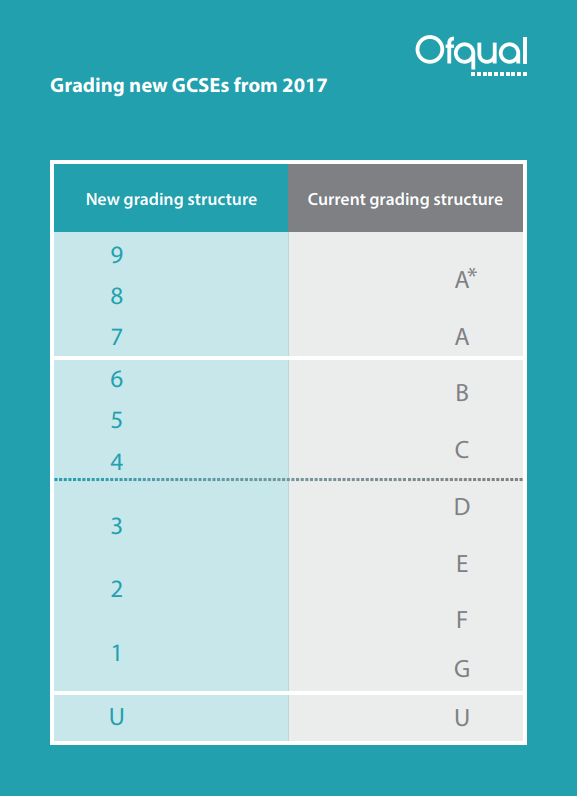

Instead of receiving grades from A* to U in all subjects, students will get numerical grades from 9 to 1 in English Literature, Mathematics, and English Language.

A grade 4 is roughly equivalent to a low C, the standard pass grade.

Meanwhile, a grade 9 is even higher than an A*. A grade 1 is about halfway between an F and a G — needless to say, it represents a pretty disastrous failure.

The government have released a helpful postcard to assist parents, students, and employers in translating the new grades.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

However, The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) advise people to avoid “direct comparisons and overly simplistic descriptions”.

Interestingly, for the subjects using the new grading system so far (Mathematics, English Language, and English Literature), students who fail will be need to continue to study those subjects if they fail to achieve a grade 4.

Do the kids still get some letters?

Yes they do. The two core English subjects and Mathematics are the only subjects on the new grading system for the time being. All other courses will keep A* to U grades.

As of next summer, most other examinations will be switched to numerical grades. These include biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, French, Spanish, religious education, geography, music and history.

But even those pupils taking their exams in 2018 won’t be fully letter-free either. Further subjects including psychology, ancient history, business, information and communications technology (ICT) and media studies will only get the new grades in 2019.

What’s with all the changes?

The changes to the way GCSEs are graded is the apotheosis of Michael Gove’s vision for education. Then former-education secretary (who left office in 2014) decided to make GCSEs ‘more rigorous’.

Along with changing the subject grades, the new system heralds in a new style of examination. Rather than studying modules and writing coursework over their final two years of school, one final exam will mostly decide Year 10 and 11 students’ grades.

In addition the content on by the new systems is more challenging, at least, that’s the idea.

The government are hoping that the school system will eventually replicate some of the strongest education systems in the world. Hong Kong and Shanghai are often seen as as paragons of what the government is attempting to achieve.

Another potential benefit of the new system is that there’ll be a greater distinction between intelligent pupils.

Those who might have scraped an A* with a tonne of hard work might find themselves with grade 7s or 8s while those who would have taken little effort to achieve an A* might be lucky enough to win a grade 9.

Why are universities unhappy?

Unfortunately, it isn’t all good news. Some universities and employers are furious about the new system. They claim that the new grade don’t have an appropriate boundary between passing grades.

For example, currently many universities demand that students have a grade C in Mathematics and English Language and Literature to win a place. Unfortunately, the new system splits grade C into two separate grades: 4 represents a ‘standard pass’ and 5 is a ‘strong pass’. This has led to confusion for some universities. UCL and KCL who once asked for Cs are now asking for grade 5s, while Manchester, Leeds, and Liverpool who used to also ask for Cs are now asking for grade 4s.

Deborah Streatfield, founder of careers advice charity My Big Career, voiced her anger at the confusion while speaking to the BBC:

It’s inconceivable that a simple task of deciding a pass has led to a ridiculous standard pass and a good pass. Universities and employers need to decide whether a 4 or 5 is the benchmark. At the moment different standards across universities will lead to a divisive landscape leading to disadvantaged students losing out again.

Rather unhelpfully, Justine Greening, education secretary, said that it’s up to universities to set their own entry criteria.

Suzanne O’Farrell of the ASCL head teachers’ union also spoke to the BBC. She suggests that schools should ‘future proof’ their students by only treating grade 5 as a pass, ignoring grade 4.

What do employers think?

Robert Coe, a professor in Durham University’s School of Education, was also critical. Speaking to the Independent he expressed a belief that ‘not much more than chance’ will separate between grades until markers have got a more solid handle on the new system:

Part of the reason for the regrading process was because the top grades had become a bit too common, and you want something that discriminates a bit more. But the trade-off is that it is more likely to be wrong, with people awarded a grade that they shouldn’t have. When you start to look, it is quite alarming. Individual subject grades can make a huge difference to someone’s whole life course. They really do matter.

Ofqual have argued that they’ll be balancing it out a little more to ensure kids receive fair grades. How they plan to juggle this balancing act is confusing to say the least and downright nonsensical at worst.

Employers are also unhappy with the changes. Seamus Nevin, head of employment and skills policy at the Institute of Directors, a group of business leaders, said that he thinks the new grades might have an effect on the employability of students in the future:

[Employers] might think, ‘What is this gibberish, and what does it mean, and how has it changed from previous grading systems? If the employer is time-poor and resource-constrained then they can, on occasions, be quite keen to get through as many [CVs] as possible. So if they have a CV that they don’t understand, then they might opt for the ones that they do.

Do we need to panic over this new system?

Probably not. It’s worth remembering that after getting onto A level courses, GCSEs don’t mean a lot, as long as you’ve passed.

Things might take a little while to adjust, but there won’t be any other option.

The GCSEs are designed to push students and make them more prepared for the world of work.

Ultimately, experiences shows us that in a few years people will probably be complaining the new system is too easy.

Then we’ll no doubt see a pining for ‘the good old days’ and everything will probably go backwards.

Until then, no one has much choice but to accept the changes and move on. So strap in and enjoy the ride, kids, you might as well enjoy it!