It’s 47 years since the UK’s so-called Decimal Day — the day the country converted to decimal currency.

Its introduction saw Britain follow most European countries’ adoption of the system and, since then, the fate of the pound has become increasingly tied to European affairs.

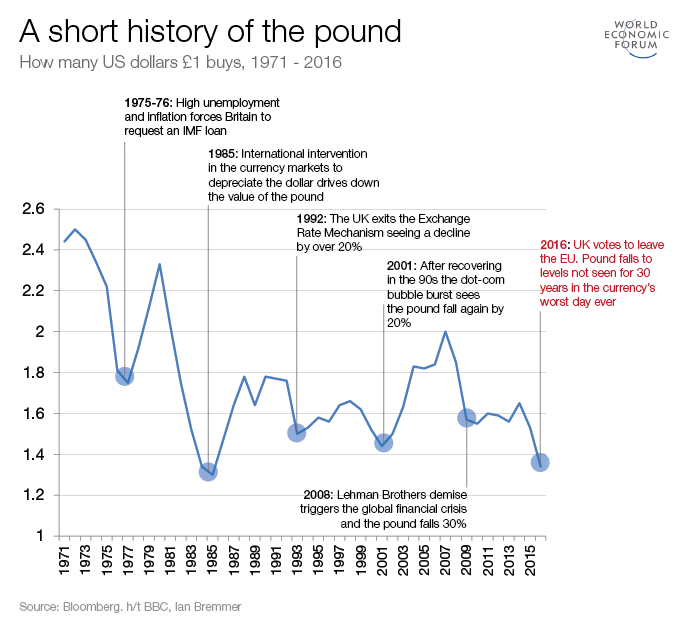

That symbiotic relationship between British and European currencies — and their politics — reached breaking-point in 2016 when Britain voted to leave the European Union, sending the pound crashing to a 30 year low against the dollar.

In a globalised economy, the pound is susceptible to a much wider influence that extends beyond its closest neighbour: the Plaza accord, dot-com bubble and 2008 global crash have all caused a steep fall in the value of the pound.

More recently, Britain’s vote to leave the EU saw the pound crash to $1.33 as investors worried how the split would affect trade links, free movement of capital, and free movement of labour.

The pound has since recovered to $1.41 at the time of writing, but the direction of its volatility remains largely tied to the latest news from Brussels.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

However, in the 47 year history of the decimal pound, this turbulence is nothing new.

Pre-decimalisation, British currency consisted of a complex system of pounds, shillings, guineas, half crowns, threepenny bits, sixpences and florins.

This currency reflected Britain’s complex history; the Romans, Saxons and medieval Kings all had a hand in shaping it.

Calls to mirror countries like France and the US, which adopted the decimal system in the 1790s, began as early as the 1800s.

Britain, however, was slow to convert.

On Monday 15 February 1971, Edward Heath’s government formally abolished the old coinage system.

To some, it was a symbolic moment of progress as Britain moved away from its Imperialistic past and into closer unity with its European neighbours.

To others, it was an erasure of tradition and marked the start of creeping Europeanisation of British institutions.

Those that feared it was the beginning of greater European integration were proved correct just two years later, when Britain voted to join the early incarnation of the European Union, known then as the Common Market.

For much of the 1970s, for reasons domestic and international, the British economy suffered. High unemployment and inflation forced Britain to request an IMF loan, and the pound’s value decreased to a low of $1.7.

In 1979, the pound finally recovered. Up until then, Britain was bound by exchange controls that restricted the ability to take money out of the country. Foreign investment suffered greatly as a result, but in 1979 Margaret Thatcher’s government abolished these restrictions. For the first time, the pound was allowed to float, rising to $2.

This free movement and full convertibility of capital — which went on to become one of the defining pillars of the EU — was a lifeline to the British economy.

That same year, the European Exchange Rate mechanism was introduced by the European Economic Community to achieve monetary stability in Europe.

However, in 1992 Britain was no longer able to keep the pound above its agreed lower limit, and John Major’s government succumbed and left the ERM on September 16.

The pound’s sharp 20% fall earned it the moniker Black Wednesday, with the UK Treasury estimating the cost at £3.4bn.

In the late 1990s, currency once again became a focal point for Britain’s identity as politicians debated Britain’s adoption of the Euro.

Ultimately, Britain rejected the EU’s shared currency — a move that many economists now think was a good decision.