Wildfires around the world, droughts and reservoirs at record low levels driven by climate change, a disrupted water cycle, and population growth mean that water is set to become a more important topic than energy when it comes to the impact of data centres on creaking infrastructure.

This is exacerbated by the fact that there is no ‘hiding from the truth’ with any equivalent to energy carbon offsets for water. There either is or is not water available for cooling – and with many European countries unable to douse their annually growing destruction from fires driven by global warming and hot, strong winds, data centres are likely to become an even hotter topic in political circles. By 2027, the OECD projects that AI will require 4.2–6.6bn m³ per year. This is more water than the entire annual use for a country like Denmark, or nearly half that of the UK.

When citizens are losing their lives and their livelihoods because of the growing impact of wildfires – ironically also accompanied by flash floods which result from heavier rainfall not being able to be absorbed by baked earth – public opinion and government policy will change. This may pose the greatest threat to the perceived glorious future of AI-powered lives, alongside other issues centered around potential job losses and cybersecurity threats.

Robert Pritchard, Principal Analyst, Enterprise Technology and Services at GlobalData, comments: “The global exuberance for AI and investment in hyperscale data centres for the future of business will before long hit a reality check when voters realise the impact they are having not just on their energy infrastructure, but increasingly on their water supplies. The general trend towards extending greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets and obfuscation through often discredited carbon offsets will not wash. We need also, in the light of ongoing cyberattacks and energy disruptions which have yet to see significant impacts on data centre activities, to consider water provision vulnerability to terrorist or activist attacks and the functioning of data centres – again, there is no obvious back-up solution like there is for energy supply.”

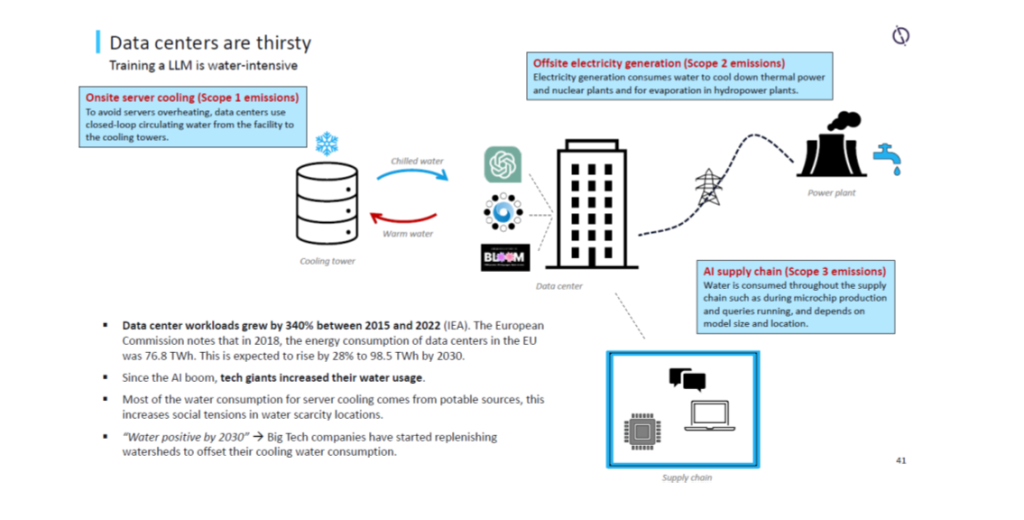

On the plus side, tech companies are looking to improve their water efficiency by alternative cooling technologies to substitute for traditional water and air cooling. Martina Raveni, Analyst, Strategic Intelligence at GlobalData, observes: “It is now well known that water use represents a significant environmental issue associated with data centre cooling that operators must consider alongside their emissions. Big Tech has been increasing its water consumption for cooling purposes since the AI boom. For example, Google and Apple increased their water usage by 28% and 9%, respectively, between 2023 and 2024. Interestingly, Microsoft’s water consumption went down by 26% in 2024 compared to the year before. New Microsoft facilities adopted a closed-loop design for direct-to-chip liquid cooling systems, they improved water usage effectiveness (WUE), and the company continued to expand its water replenishment activities.

Several technologies and innovations are being explored as alternative cooling solutions to reduce water use. These include immersion cooling using dielectric fluids and direct-to-chip cooling.

In direct-to-chip cooling, the coolant flows through a plate (the cold plate) that is in direct contact with major heat sources, such as individual chips. A specialised form of liquid cooling is immersion cooling, where an entire server rack is immersed in a non-conductive liquid, a dielectric fluid. A dielectric fluid is a thermally conductive but not electrically conductive fluid. This cooling method allows for efficient temperature management. It has the potential to reduce reliance on water and save space. However, it might not be suitable for all types of data centres, and the associated leaks represent a significant risk.

Although liquid cooling is the new frontier, innovative approaches have started to appear in the market to cool down hot data centres. An example is using ceramic components forcircuit boards and semiconductors, materials that are effective at heat dissipation. Maruwa, a Japanese ceramics company, produces ceramics that are handy for electronics operating in data centres, especially those where AI algorithms are run, since they can reach high temperatures.

Furthermore, there are environment-based cooling strategies, which use naturally cold settings to cool equipment. One example is underwater data centres, where sealed data centre units are placed deep in the ocean, harnessing the ocean’s natural cooling capabilities.

However, data centres require laborious maintenance, and the fluctuation of water temperatures presents potential downsides. In 2015, Microsoft started a research project, Project Natick, to build underwater data centres. In 2024, the company discontinued it, planning to apply the insights gained from this project to other areas. Nautilus Data Technologies (NDT) is a California-based start-up that, in 2021, opened a floating barge data centre in Stockton, California, giving it access to large volumes of cool water. I expect investments in these technologies to grow, driven by the need for energy efficiency and regulatory pressures. Companies that develop and deploy these cooling technologies will likely see increased demand.”

For a detailed analysis of the cooling technologies adopted within data centers, see GlobalData Deep Dive into The Environmental Impact of Data Centers.

In conclusion, GlobalData sees access to an evolving range of alternative cooling solutions as key to addressing what looks to be a significant potential challenge as water resources globally come under increasing demand.