In the two weeks since Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were poisoned in Salisbury, British-Russian relations have tumbled to their lowest point since the Cold War.

The British Government accused Moscow of orchestrating the incident – described as “a war-like act” – and began to outline retliatory measures. World leaders joined Theresa May in denouncing Russia for an attack which “threatened the security of us all” and vowed to take action. Meanwhile, the Russian press and politicians alike denied any involvement, mocking and promising to retaliate for what they saw as hysterical attempts to paint Russia in a negative light.

It is possible, if not probable, that the full facts behind the attack on the Skripals will never come to light. But research shows that reactions to the crisis so far tie into broader trends in how the world views Russia, and in how Russia views itself.

Russian voices have repeatedly claimed that current criticism is little more than anti-Russia bias. This may be a convenient excuse but the observation of global anti-Russian feeling is rooted in reality. According to Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington DC, Russia was regarded in a broadly negative light by much of the international community before the current crisis.

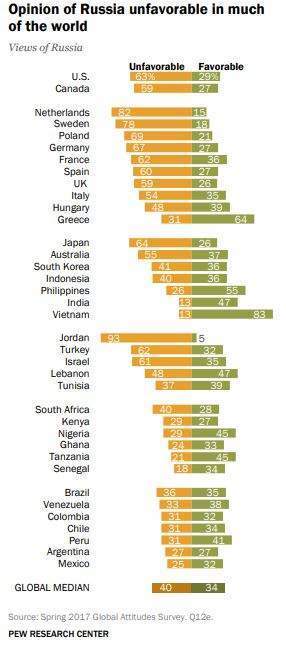

In 2017, as part of its annual ‘Global Attitudes’ survey, Pew Research Center asked respondents from 37 nations outside Russia how they viewed the country. Critical opinions of Russia dominated, with 22 of the nations surveyed reporting more unfavourable than favourable opinions of Russia.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe countries most vocally standing against Russia in the current row – Britain, France, Germany and the United States – are all from the regions that exhibit the most distrust of Russia as a whole. In North America, 63% of Americans and 59% of Canadians hold negative views of Russia, while in Europe a media of 61% showed anti-Russian sentiment. European countries also expressed increased perceptions of Russia as a security threat to countries elsewhere, although most saw threats such as ISIS as being more significant.

The same research shows how views of Russia have changed significantly in some countries, including the UK. Dr Richard Wike, Director of Global Attitudes Research at Pew Research Center, said:

Attitudes toward Russia have also become more negative in the UK in recent years. In 2011, 50% of those we polled in the UK had a favourable opinion of Russia, compared with just 26% in 2017.

This change in attitude happened over a period where Russia has become increasingly belligerent on the world stage, including the annexation of Crimea (2014), military intervention in Ukraine (2014), military intervention in the Syrian civil war (2015), repeated allegations of cyber attacks, and accusation of meddling in Brexit and the US presidential election of Donald Trump (2016).

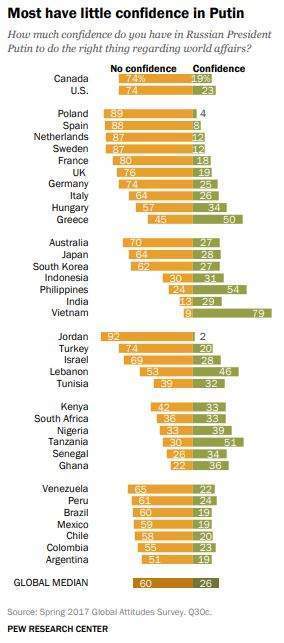

Negative views of Russia are tied closely to perceptions of Vladimir Putin, Russia’s strongman President who is up for re-election this Sunday. Globally, Pew Research found that 60% of respondents expressed no confidence in Putin to “do the right thing regarding world affairs”.

The speed with which Britain and supporting nations implicated Moscow in the Skripal case may well be rooted in this general mistrust of the Russian leader.

Similarly, pre-existing attitudes within Russia help to contextualise Russian reaction to the current situation.

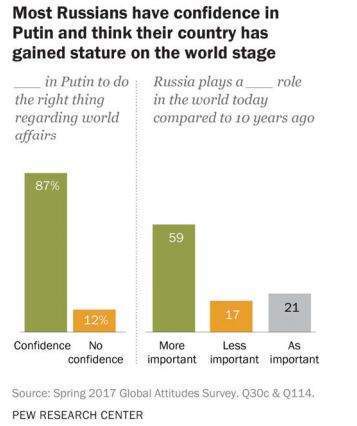

Pew Research Center’s ‘Global Attitudes’ survey for 2017 showed great regard for Putin within Russia, particularly in relation to international issues (in other areas, such as the economy, approval was less widespread), often in direct opposition to views expressed elsewhere.

A large majority of respondents (87%) expressed confidence in Putin’s ability to “do the right thing regarding world affairs”. This was accompanied by a majority (59%) believing that Russia today played a more important role in the world than a decade previously.

The level of Russian confidence in Putin has risen in recent years, most notably between 2011 and 2016, as Putin enacted increasingly controversial foreign policy. During the same period UK attitudes towards Russia shifted downwards and global attitudes were broadly negative.

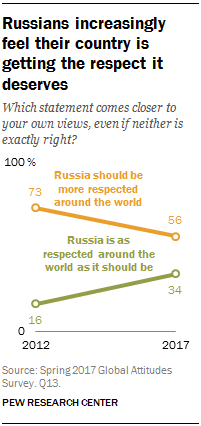

Across roughly the same period, Russians also exhibited higher levels of belief that their country was appropriately respected by others.

These findings suggest several things: that Russians’ approval of their leader is bolstered when it starts falling elsewhere; that Russians broadly agree with Putin’s position on foreign affairs; and that, for Russians, global disapproval and global respect are not at all mutually exclusive.

Attitudes to the Skripal case are no different. As Putin continues to refuse to engage with the demands of Britain and others over the Skripal case – making no attempt to meet May’s deadline for an explanation or to mediate discussion – it is hardly surprising that Russians react with outrage and derision.

For other world leaders, being implicated in a major diplomatic row days before a presidential election could be a recipe for disaster. Not so in Russia. If anything, this crisis will work in Putin’s favour.