Last night in the UK, Lubaina Himid won the Turner Prize. At 63 years old, she became the oldest winner of one of the most celebrated prizes in British art. She also becomes the first ever black woman to win the prize.

Based in Preston, Himid is a professor of contemporary art at the University of Central Lancashire. In general, Himid’s work focuses on the prejudices faced by ethnic minorities this includes addressing colonial history, racism and institutional invisibility.

However, while Himid is earning praise and acclaim for her work, the Turner Prize in general is often a subject of scorn in the art world. An art critic for the Observer, Matthew Collins, once wrote:

“Turner Prize art is based on a formula where something looks startling at first and then turns out to be expressing some kind of banal idea, which somebody will be sure to tell you about. The ideas are never important or even really ideas, more notions, like the notions in advertising. Nobody pursues them anyway, because there’s nothing there to pursue.”

Artists and art critics often mention their desire for art to be ‘daring’, ‘challenging’, or ‘offensive’. But how far is too far in the world of art?

Well, a painting by Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is forcing some to grapple with these issues.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataMetropolitan Museum of Art, Thérèse Dreaming, and Mia Merrill

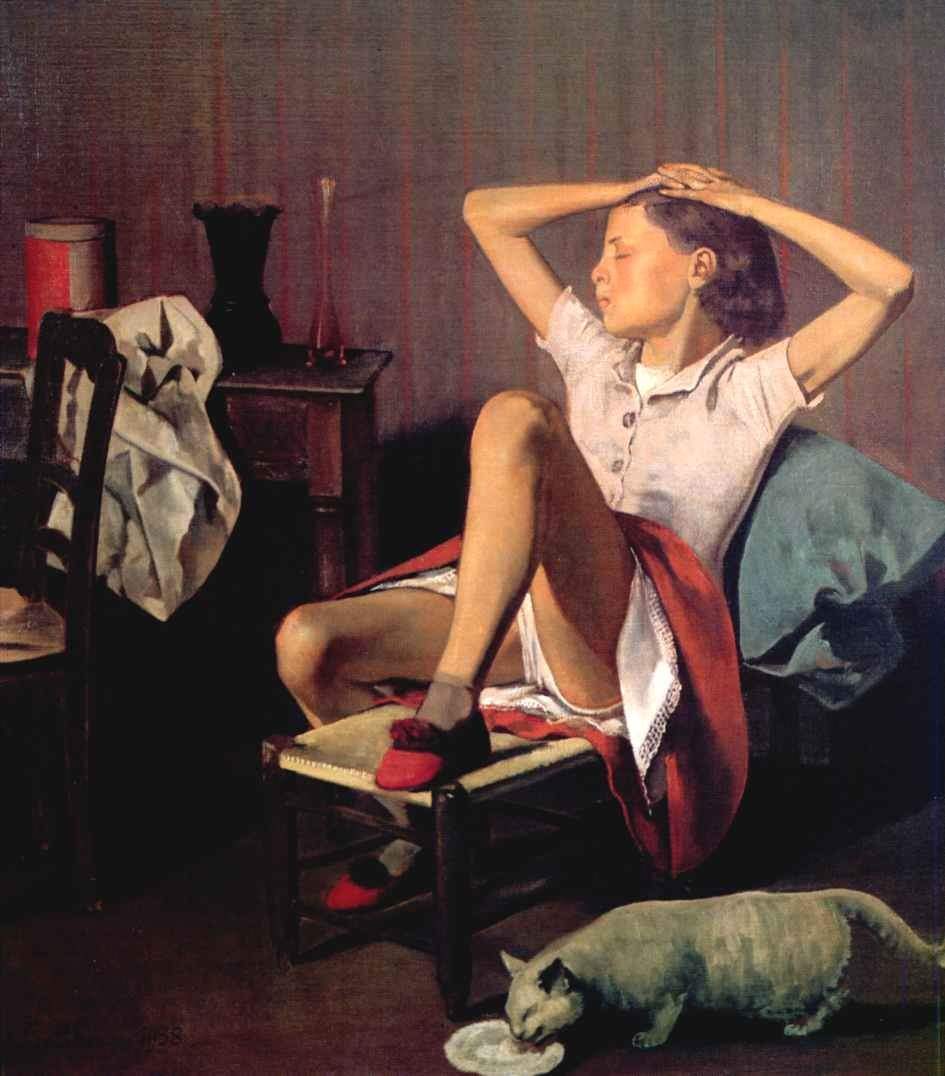

The work of art is a piece from 1938 titled Thérèse Dreaming. It depicts a prepubescent girl reclining on a chair. At her feet, a cat licks milk from a saucer on the floor. The painting is believed to be a depiction of Thérèse Blanchard, a Paris neighbor of Balthus. However, what’s really worked up visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the position of Balthus’ subject.

As the girl reclines on her chair, her legs are open exposing her underwear.

The controversy was first raised by New York resident, Mia Merrill, after she saw the painting on a visit to the Metropolitan Museum. In Merrill’s eyes, the painting ‘romanticizes the sexualization of a child’. With the continued controversy over the issue of sexual assault, especially in light of the #MeToo trend that saw women sharing stories of sexual assaults and unwanted advances made towards them, the issue is more pertinent than ever.

The petition to take down the painting:

Merrill’s exception to the artwork struck a nerve with art lovers around the world after she started a petition asking the Met Museum to remove the painting.

She argues that the painting should either be taken down or placed in further context. Merrill suggests that a small plaque with words such as “Some viewers find this piece offensive or disturbing, given Balthus’ artistic infatuation with young girls” would be just as effective.

I put together a petition asking the Met to take down a piece of art that is undeniably romanticizing the sexualization of a child. If you are a part of the #metoo movement or ever think about the implications of art on life, please support this effort. https://t.co/gcCAFDe749

— Mia Merrill (@miazmerrill) November 30, 2017

Nearly 10,000 supporters have backed Merrill’s petition at the time of writing. Comments on the petition included the following:

“It is time to change the male gaze – particularly when that gaze objectives girls. It is simply not good enough to say its provocative – look for other work that is provocative for different reasons. Stop putting girls at risk.”

“In the context of mass sexual abuse claims and the huge gender inequality in art galleries (in terms of visual representations and female artists) this is simply not the kind of image we need to see rigt now. The message is all wrong but galleries are notoriously reluctant to move with the times and address gender inequality.”

Metropolitan Museum of Art’s response:

However, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has steadfastly refused to remove the painting. Spokesman Kenneth Weine said in a statement:

“[Our] mission is to collect, study, conserve, and present significant works of art across all times and cultures in order to connect people to creativity, knowledge, and ideas.”

“Moments such as this provide an opportunity for conversation, and visual art is one of the most significant means we have for reflecting on both the past and the present.”

The National Coalition Against Censorship has hailed the decision. In a statement it said:

“Recent cases of censorship, including the threats of violence that forced the Guggenheim Museum in New York to remove several exhibits, reveal a disturbing trend of attempts to stifle art that engages difficult subjects. Art can often offer insights into difficult realities and, as such, merits vigorous defense.”

However, Merrill hasn’t counted her petition as a total failure. In an update, she explains that a plaque explains the context of Balthus’ work would be a victory.

To be fair, Balthus’ work has attracted similar criticism before. The Met hosted a Balthus exhibition in 2013, Balthus: Cats and Girls — Paintings and Provocations, which attracted similar critique. In their review of that exhibition, the Guardian wrote:

“The girls are self-possessed and serious, and Balthus always denied any hint of paedophilia. But get real: these are erotic images of children. Some, especially the Thérèse portraits, show real invention and even a little humour that make them difficult to dismiss outright. Others, especially the mannered domestic scenes of his later career, are barely competent acts of voyeurism.”

As ever with art, it really is up to the reader to decide. However, as long as museums continue to display art, debate will always rage about its role and purpose in our lives.